Wisconsin Standards for Environmental Literacy & Sustainability state that “students engage in experiences to develop stewardship for the sustainability of natural and cultural systems” (ELS.EN7). Take a closer look at the learning priorities in this standard and you will find that students are not just engaging in stewardship experiences, they are designing the experiences. How do we make this shift from an educator-directed experience to one led by students? Inquiry.

What is inquiry?

In the book Inquiry Mindset, the authors share a definition of inquiry as “the dynamic process of being open to wonder and puzzlements and coming to know and understand the world” (MacKenzie, 2018). Wow. As educators, we often lament the fact that students aren’t curious anymore and don’t slow down to experience awe at the wonders in this world. Could more integration of inquiry address this?

What does inquiry look like in practice?

“Inquiry-based learning is a process where students are involved in their learning, create essential questions, investigate widely, and then build new understandings, meanings, and knowledge” (MacKenzie, 2018). This inquiry-based approach puts students at the center of the learning process, rather than the end receiver of information. Through inquiry-based learning, students construct understandings rather than memorize them, and share this new knowledge with authentic audiences.

Inquiry-based learning requires student-driven exploration of real-world issues and phenomena, sharing results with authentic audiences, and reflecting on the experience. In inquiry, students are uncovering the learning; the teacher’s role is more of a guide or facilitator rather than presenter or lecturer. An inquiry-supportive classroom culture is one where struggle and developing wrong conclusions are not signs of failure but expected and essential parts of the learning process.

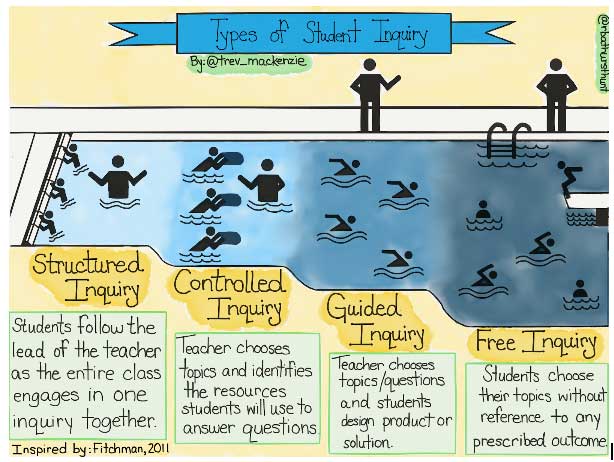

MacKenzie outlines four types of inquiry (see graphic) to meet teachers and students where they are: 1) structured inquiry, 2) controlled inquiry, 3) guided inquiry, and 4) free inquiry. When students (and teachers) are not used to leading their own learning, moving through these four types of inquiry can provide the scaffolding needed for success.

For example, students may observe flooding in one area on the playground.

- In a structured inquiry, the teacher may lead the entire class through investigating this phenomena by exploring when and why flooding occurs and developing solutions to mitigate the water.

- In a controlled inquiry, the teacher may help the class develop a number of questions to explore the topic and then provide a variety of resources for students to develop answers and possibly solutions.

- In a guided inquiry, students may form their own groups to explore different aspects of this topic and each might develop a different solution. Students may share their plans with the grounds manager. The grounds manager shares additional information with students that help them rethink their plans and groups go back and revise.

- In a free inquiry, students may choose any related topic and follow his or her own path of learning.

Through all of these types of inquiry, students may erroneously identify the cause and/or effect, but through questioning and reflection during research and development, they gain new information to construct knowledge and revise their understandings.

How can inquiry be integrated into existing programming?

Authentic learning takes time. In order to make time for inquiry, educators will have to weed out non-essential activities. However, because inquiry-based learning is such a rich learning experience, educators will also find they can braid together several concepts and skills through the process.

Developing good questioning protocols is an essential part of supporting inquiry in the classroom. When students ask questions about what they are discovering, educators answering those questions with questions can help the student consider and analyze their own conclusion or wondering rather than expecting you to tell them. Questions like “Why do you think that?” “What made you draw that conclusion?” “Where does that question come from?” can not only help you as an educator uncover misunderstandings, they can also help the students reflect on their own thinking and shift course if necessary. The Question Formulation Technique and the Beetles Project both have tools to help educators become better at asking questions. (I especially like the Beetles’ meaning-making discussions and their support for guiding explorations).

Integrating inquiry takes time and practice. To get started, choose one activity or unit rather than trying to redesign your entire course. There is no one way that works for everyone. Read blogs and books about different approaches and find something that works for you and your setting.

Here are some books and articles to get started:

- Inquiry Mindset by Trevor Mackenzie and Rebecca Bathurst-Hunt

- Dive into Inquiry by Trevor Mackenzie

- The Curious Classroom: 10 Structures for Teaching with Student-Directed Inquiry by Harvey Daniels

- Edutopia inquiry-based learning articles

- Getting Smart blogs on inquiry

Victoria Rydberg, Guest Writer

Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction

Environmental Education and Service-Learning

Advertising Disclosure: Please note that we may use affiliate links to retailers which yield a commission for us at no extra cost to you. We only recommend products we've used that support our mission. As an Amazon Associate FIELD Edventures earns from qualifying purchases. Your purchases support taking learning outdoors.